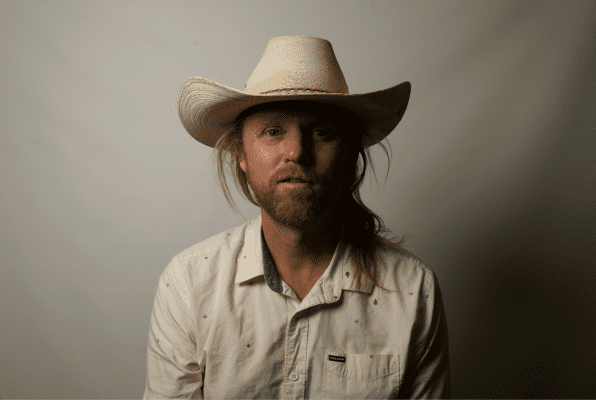

No South Bay food enthusiast can have failed to notice a sharp improvement in the quality of local restaurants in recent years. Ambitious chefs, more committed owners and more discriminating diners are obvious factors. Another, less obvious factor is Louis Skelton. If you’ve been delighted by the dramatic ambience of a local restaurant, more than likely Skelton had a hand in its design.

It’s not possible to pick out a Skelton restaurant because he prides himself on not having a signature look.

“I’ve done everything from the rustic look of Four Daughters Kitchen (in Manhattan) to the very contemporary Shade Hotel (in Manhattan Beach). I don’t have any particular stylistic signature – I just want people to walk through my restaurants and feel like they’re comfortable, that there be have visual cues so they know what to do, what kind of place they’re in.”

“Your mood for a particular experience determines how you will feel about a restaurant on any particular night. It’s like theater — there are times when you want serene, times when you want daring and experimental – sometimes you want a revival, the comfortable, secure experience rooted in culture. Sometimes you want an intense drama, something British and cerebral, and sometimes you want to go see ‘Hair’ — loud, boisterous and fun. The experience you’re set up for that evening determines what theater you’re going to go to.”

And for those who aren’t sure what they want? Sometimes it’s best to just walk into a place and see if it calls to you. As Louis Skelton puts it, “If you dislike a place you used to enjoy, it may not be the food, it may be the whole experience you are reacting to.”

Where’s the kitchen?

“In one case, I had serious talks with a celebrity owner who wanted to recreate a memory of her childhood. She had not put a minute into thinking about what route the servers would take from the kitchen to the tables, or much else. Other owners have an idea of what they generally want, but they don’t know a thing about the materials or techniques. When I start discussing the scalability of the kitchen, that’s a whole new concept to them. They usually get the idea after we discuss it – that the design of a restaurant can help make it successful. If you have a kitchen with stations so far apart that you can’t operate with fewer than four people, you’re going to have trouble every day between 2 and 5 p.m. when there might be only three people in the dining room. “

Such concerns, despite being unseen, affect every diner, while other aspects of design are important even though they are felt on a subconscious level. Skelton often invokes the theater in describing the experience.

“The way they proceed from their car through the front door to their seat is part of setting the stage. Your first impression sets your idea of the restaurant; if there is going to be a surprise, let it be a delight. Let it be something interesting, something that makes them say ‘wow,’ I would have never thought of that. There are some places that are overtly stage sets, like restaurants on a wharf that go for a nautical flavor. That’s more subtle now than it used to be. There used to be plenty of places that went over the top with nautical artifacts. That was extraordinarily popular through the ‘70s and into the ‘80s, when a more minimalist style became fashionable. I remember the Bombay Restaurant in Beverly Hills, which had these long spaces of blank pastel wall broken up by one little statue of Ganesha with a light on it. That minimalist style of décor was meant to help you focus on your food instead of your surroundings.”

A designer can include visual cues that are apparent only to those in the know, as Skelton designed into newly opened Charlie’s, the former Cialuzzi’s Italian restaurant in Redondo Beach.

“At Charlie’s we didn’t want to shout New York, but we wanted to include a lot of references that any New Yorker would recognize. There’s a New York City manhole cover just inside the front door, and some other visual treats. The intent of the bar area was to keep it very open and let the people be the art. There’s a little bit of wood treatment around the beer taps, as there would be in an old place there, but it’s all subtle.”

New York is easy to invoke, even to caricature – what about the South Bay? What are our visual cues?

“One of the things is open-air dining – not necessarily an open patio, but a chance to enjoy the environment. My college professor from 30 years ago, Harwell Hamilton-Harris, who designed Chadwick school, taught me that the indoor and outdoor have to relate to each other, even if it’s just the passage between one and the other. This is traditional in Asian architecture, and it fits the way we live here. It might be a sliding window or a series or doors, like at Rock’n Fish (in Manhattan), or where the whole front of the restaurant opens up, like at Simmzy’s (in Manhattan) and the new Hot’s Kitchen in Hermosa.

A flair for drama

Skelton’s architectural career path started in a little town in the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina, sparked by the kindness of a mentor.

“I became interested in architecture when I was nine years old, thanks to my next door neighbor who was a shop teacher. He taught me how to use tools, how to make wood into things. By the time I was 10, I was a pretty effective apprentice carpenter. One day we walked down to a construction site where they were building a foundation for concrete to be poured into. A car drove up and a man got out with plans in his hands, and I asked, ‘Who’s that?’ My neighbor said, ‘That’s the architect.’ I thought I liked his job better than the concrete guy who was sitting in the dirt, so I went home and announced to my mom that I was going to be an architect. My mom didn’t take me very seriously, but I stuck to that thought, and I never considered much else.”

His interest intensified as he learned more. At the same time, he developed a strong interest in theater that turned out to be unexpectedly useful. He was still in high school when he saw a picture in an encyclopedia that revealed the potentials of modern architecture.

“I was looking in an encyclopedia and saw a picture of (Frank Lloyd Wright’s) Fallingwater. That was the most interesting thing, to have a waterfall in the house, to use the stone from the area so it fit the environment. I started reading about Wright and got more and more interested in modern work. I started reading about the Bauhaus movement – after the Nazis kicked them out of Germany, many of the instructors moved to Black Mountain, North Carolina. They built a camp there using extraordinary contemporary architecture, like nothing I had ever seen before. I applied to architecture school at NC State and was accepted, and some of those Bauhaus architects were my professors in my freshman year. It opened up a small town mountain boy to another world.”

Profession by and of design

One of those professors gave Skelton a chance to put what he was learning into practice.

“While I was in college, I got married and worked at a firm owned by one of my professors. He didn’t do design work himself, so it got thrown onto my desk because I was the senior architecture student. One of our projects was a Shoney’s Big Boy, and after I finished that I did some mom and pop restaurants and a couple of lounges. This developed my interest in what restaurants did, and I used my theater background to put my ideas together, because to me a restaurant is nothing more than a stage set. You walk into a dining room and there are players upon the stage, people who are there to make you feel comfortable and entertained, to take satisfaction in a meal, which is a basic human need. Everybody comes to the theater with different experiences and leaves with a common experience. When I realized those parallels it changed the way I thought about design.”

Skelton graduated during a recession, and the only job he could find was at McDonald’s – not flipping burgers, but as an architect.

“I hired on for three years doing construction management, design work and site work. In the beginning that involved little creativity, but I began to personalize their locations to fit their surroundings. In Virginia Beach, I put boards and battens and a walkway around it and made it look like a beachside antique or nautical shop. At another place up the coast, the floor level had to be four feet above the parking lot because the area flooded sometimes. I put gangplanks up to it and made it look like a wharf. In Brevard, N.C., I covered the building with native fieldstone, which was the first time they’d ever worked with stone. The guys at corporate in Chicago kept looking for my next plan, wondering, “What’s he gonna do next?” Out of the 40 restaurants I had designed, 20 had a special exterior.”

Post quarter-pounders

After he left McDonalds’ and became a licensed architect, Skelton spent a few years on projects as diverse as designing prefabricated restaurants to be shipped around the world, managing the construction of 19 floors of the Jimmy Carter office building in Atlanta, and starting a practice specializing in adapting old buildings to different uses. By 1982 he was happily settled in a 200-year-old house in Columbus, Ga., had won a place in Who’s Who in America, and was artist in residence for the local school system. That’s when he received a call from a firm in Los Angeles. The company wanted to open a design department in Atlanta and wanted him to head it – would Skelton fly out for an interview?

“It was 38 degrees with 10 inches of snow when I left Atlanta, and I arrived on a 71-degree California evening. I had the interview the next day, we took in the Queen Mary and Disneyland, and I went home. A week later they called with an offer – not to head their design department in Atlanta, but in California. My only question was, ‘When do I start?’ That was Friday night my time, and I was at my desk Monday morning in California. I turned my life around in 72 hours and never looked back.”

The attitude toward California was markedly different from even the most cosmopolitan parts of Georgia and the Carolinas, and it took a while for him to get used to it.

“There (the South), I would finish an interview and their first question would be, ‘Now, who was your grand-daddy?’ They want to know if you’re part of the old South. In California it would be, ‘How fast can you do it and how much will it cost?’ My experience with McDonald’s actually served me well. There, it was always about how well you could do it, not who you knew.”

Skelton spent a year designing restaurant interiors for the company, then decided to start doing it on his own. Since then, he has designed all manner of structures, but he continues to specialize in the hospitality field. His credits include restaurants in all 50 states, and brewpubs in over 20 countries, as well as local projects such as the dining space at Shade Hotel and restaurants Simmzy’s, Mediterraneo, Rock’n Fish, Blue 32, Mucho, and Hot’s Kitchen.

View the Skelton family of restaurants.