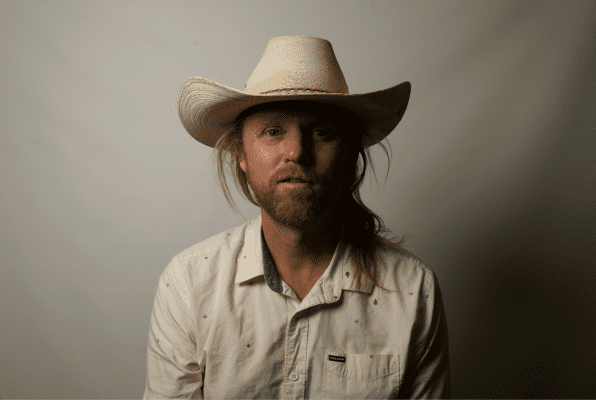

The first time Ebiye Udo-Udoma saw handball being played was during the 2008 Beijing Olympics. He was a highschool student at the time and didn’t know much about the sport — but he knew he wanted to be a professional athlete.

Today, Udo-Udoma is one of the top players in the world of Beach Handball, a variation of indoor handball but played in the sand and with slightly different rules. He’s lived near Hermosa Beach since 2016, where both the women and men’s National Beach Handball teams are now based.

“This is a great place to compete in beach sports at a high level,” Udo-Udoma said.

Beach handball is immensely popular in Europe and Brazil, homes to some of the best teams in the world. In the past few years, Udo-Udoma and his teammates have seen an opportunity to make their mark in a relatively young sport that most Americans haven’t even heard of yet.

The Oregon native Udo-Udoma has traveled to over 15 countries to play handball in the past six years, including Russia, Qatar, Trinidad and Brazil. After COVID-19 stifled plans to travel and compete in championships this year, Udo-Udoma and some of his teammates began a weekend training camp on the beaches of Hermosa; to not only stay in shape, but to make beach handball accessible to more people.

In 2016, the U.S. beach handball team traveled to Venezuela for the Pan American Beach Handball championships. In a major upset, the US team scored a semi-final win over Venezuela and went on to win the championship, beating Uruguay the next day.

“I’m not sure I’d be talking to you right now if we didn’t win that game, that’s how significant it was for the sport In the US,” Udo-Udoma said. “It was an amazing experience.”

Handball has been described as soccer played with hands, water polo without water and even hockey without sticks. But it’s more complex than those simple comparisons, combining elements of basketball, rugby and football.

The United States National Handball Team hasn’t qualified for the Olympic Games since 1996, when they placed ninth. They’ve only qualified for the Handball World Championships six times since their first appearance in 1964.

“I can’t put my finger on what it is that makes Americans hold back from the sport,” Udo-Udoma said. “It seems like the quintessential American sport: a combination of throwing, passing, catching and dribbling. It’s all the things we do in every other sport infused into a tight package.”

Udo-Udoma said a lack of national sponsors and funding has put the U.S. at a disadvantage relative to teams in Europe and South America, where kids grow up watching handball tournaments on television and are encouraged to play from a young age.

“We’ve never been able to get over that hump of getting it on television, getting it into the NCAA and actually making it a popular school sport,” Udo-Udoma said. “It’s been getting over that hurdle that’s been a struggle for us.”

Indoor handball has been regularly featured in the Olympic Games since 1972, with a women’s division added four years later.

Staci Self began playing indoor handball after seeing it on television in the 2012 Olympics. She played for four years before moving to Southern California in 2016, jumping right into beach handball.

“At my first tournament I was determined to play something other than goalie. I had been a soccer goalie all of my life and wanted something new,” Self said. “But once a goalie, always a goalie. I ended up back between the posts, saying, ‘Okay, I’ll play goalie for one half, then I’m out.’ That was 2012.”

Both the men’s and women’s U.S. beach handball teams began to pick up momentum before games started getting canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic in March. As case numbers climbed, Udo-Udoma had to cancel trips to Italy and Brazil. He and teammate Charlie White, began training in Hermosa when the beaches opened up in May.

“COVID killed our 2020. We haven’t played since February and we had a world championship scheduled for July in Italy,” Udo-Udoma said. “But for us as athletes, we have to train as if we could play at any moment. So even though we couldn’t train the team in the South Bay like we normally would, we had to do something.”

The teams have also stayed in touch with weekly Zoom meetings, where the players analyze game footage together as a team.

“While not the same, it has broadened our handball knowledge as well as of each other as teammates,” Self said.

Two teams of seven face off in an area slightly bigger than a basketball court. Opposing teams hope to score through goals at either end by throwing the ball into the goal or by jumping and diving into it. Indoor handball players pass or dribble the ball to avoid traveling while making their ways down the court, much like basketball.

Beach Handball by comparison is a relatively young sport, with the first European Championship taking place in 2000, while the rules weren’t internationally codified until 2002. It was up for inclusion in the 2024 Olympics, but was denied on December 7.

Beach handball is known as high scoring, fast-moving spectator sports where professional teams regularly score upwards of 30 points a game. However, beach handball can be quite different from regular handball; the sand all but eliminates dribbling and instead encourages players to dive and make riskier jumps.

The weekend training camp is expected to return to Hermosa Beach in January, or as soon as pandemic restrictions permit. Practices are open to anyone interested in learning the game. Follow @RipBeachHandball on Instagram for up-to-date information on the training camp. ER