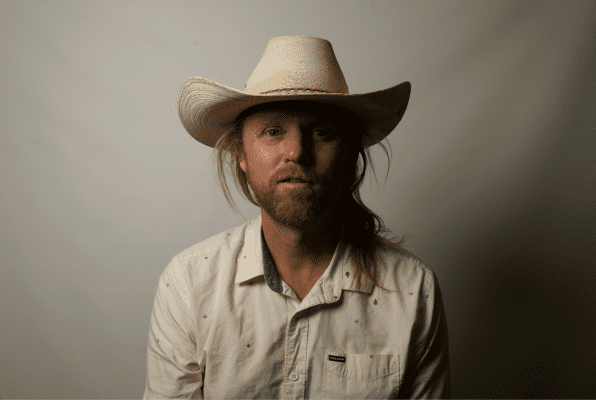

by Ryan McDonald

If ever a life called out to be transformed into a podcast, it is that of Rick “Raz” Rasmussen, a towheaded trafficker who jet-setted from jungle to red carpet before being gunned down in Harlem following a botched cocaine deal. He was 27, not far removed from a comfortable childhood in suburban Long Island. He was also a former U.S. surfing champion.

Rasmussen’s appetite for danger is apparent from his first appearance in Thad Ziolkowski’s new book “The Drop: How the Most Addictive Sport Can Help Us Understand Addiction and Recovery.” It is September 1975 and Ziolkowski is on the beach in Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, awaiting his heat at the East Coast Surfing Championships. He sees Rasmussen “kick-stall inches from the rusty steel groyne and pull into a meat-grinding barrel. Only the tip of the nose of his board is visible for an improbable stretch, then the wave shuts down like a piano lid.”

On the one hand, that Rasmussen would be dead just seven years later hardly seems surprising. His reckless display suggests an indifference to the calculus that helps most people keep their spines intact — a life lived “constantly on rail” in one of surf speak’s many felicities. Yet Rasmussen’s edge-pushing derring-do could also belong to the sort of person who seems ecstatically attached to living, the people, as William James put it, who are always “passionately flinging themselves upon their sense of the goodness of life.” (Rasmussen would also seem to have a vested interest in staying healthy, if only in the hedonistic pursuit of the deeper tube, the more critical turn.)

“The Drop” is full of sketches of characters like Rasmussen: those whose lives in the ocean burned so brightly as to appear needless of the enhancement of drugs and intrigue, but who are nonetheless sucked down and into them as if by a sinking ship. The book is also an elegant distillation of the fascinating science of addiction, and an episodic memoir that reckons with the author’s own traumas and eventual sobriety.

Ziolkowski will be appearing Tuesday evening in a Zoom event sponsored by Manhattan Beach’s {pages}: a bookstore. He’ll be joined in a conversation with William Finnegan, the author of the 2015 Pulitzer Prize-winning surf memoir “Barbarian Days.” Like “Barbarian Days,” “The Drop” features a journey to surf obsession in a time quite different from our own, when surf schools dot the coast and surfing has partially (though not entirely) shed its dangerous mystique. Ziolkowski learned to surf after his parents divorced and he moved with his mother and stepfather to Florida’s Space Coast. He falls in with a crowd of druggy dropouts, including his surf shop sponsor, who is put away after trying to sell 200 pounds of marijuana to an undercover cop.

But unlike “Barbarian Days,” which skips across the globe from reef pass to point break in jealousy-inducing descriptions of beauty and emptiness, much of the action of “The Drop” takes place inside the mind and heart. In his own life, there is Ziolkowski’s younger brother Adam, who, after the suicide of their stepfather, drifts into instability, “like a tiny nation following the toppling of a strongman.” And he delves into the darkest moments of notable surfing addicts like Andy Irons and Jeff Hakman. As a surfer, I had always known that surfing had plenty of drug problems. But finding them compiled into one place, as Ziolkowski has done, leaves a powerful impression.

For some of these stories, Ziolkowski relies on previously published books or films, including the recent documentary “Andy Irons: Kissed by God.” But for others, he is able to interview the subjects themselves. Not surprisingly, these are the strongest vignettes, none more so than the section on Tom Carroll, an Australian world champion who descended into addiction to coke, and then methamphetamine, after his professional career ended and the gilt of competition and adoration had rubbed off. Carroll eventually got clean, and is now open about his addiction and dedicated to helping others overcome theirs. The pursuit of drugs offered him a fleeting, physical rush of relief, but was also clearly filling some deeper, unmet need. “‘My ice dealer, in [Sydney suburb] Mona Vale, I remember getting some from him and we were having a pipe together, and he looks at me as he’s lighting the pipe and says, ‘No one understands, do they, Tom? No one understands,’” Carroll says.

Ziolkowski’s book is alert to the ways in which surfing can be both curse and cure. His journey takes him into the world of surf therapy, including a stint volunteering with the South Bay-based Jimmy Miller Memorial Foundation. (Local readers may laugh out loud, as I did, when he compares Kevin Sousa, a Hermosa Beach resident and the foundation’s program director, to “a hipster football coach.”) He comes away feeling better himself, the so-called volunteer high, and convinced of surf therapy’s promise. He also references the concept of “blue mind,” an idea of TED Talk-ish buzz popularized by author and marine biologist Wallace J. Nichols, that the scarcity of water in humans’ evolutionary history means just being near a babbling brook or lapping tide can be deeply soothing. “Water and meditation,” Ziolkowski writes, “are wedded forever, as Ishmael observes in Moby-Dick.”

It’s true that Ishmael is able to find a Zen-like satisfaction for moments of his journey on the Pequod. Describing Ishmael’s watch duty from the mast-head, Melville sounds almost as though he is touting a digital detox, a rehab regimen for the Screen Time Era: “For the most part, in this tropic whaling life, a sublime uneventfulness invests you; you hear no news; read no gazettes; extras with startling accounts of commonplaces never delude you into unnecessary excitements.” These moments, however, come when the ocean is still, when “everything resolves you into languor.” These are the doldrums most challenging for the committed surfer to endure, the empty stretches in which there seems no reason to rise at dawn. They are the opposite of time in the barrel, a consuming onslaught of sensory stimulation that produces heart-pounding elation but also vague disappointment at the world outside the tube. Ishmael, the narrator of a tale best known for a captain whose single-mindedness resembles that of an addict searching for a fix, connects the desire to be on the water to the story of Narcissus, the man who drowns in pursuit of his own reflection: “That same image, we ourselves see in all rivers and oceans. It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life.”

***

Ziolkowski is the associate director of the Leon Levy Center for Biography at the City University of New York. (On July 8, the Center will be hosting a Zoom event about the surf memoir genre featuring Ziolkowski, Diane Cardwell, author of “Rockaway: Surfing Headlong Into a New Life,” and the South Bay’s Michael Scott Moore, author of multiple books about surfing and “The Desert and the Sea,” his account of being kidnapped by Somali pirates.) A poet and a novelist, he has a gift for vivid imagery, such as when he compares paddling for a wave to “running alongside a wild horse in order to leap on its back,” and an eye for the telling detail. He evokes the Alphabet City bodega where he used to buy cocaine over the counter by recalling that “in warm weather, the door was held open by a length of frayed twine.”

Writing about surfing has long suffered from inaccuracies and fetishizing that are difficult to avoid for the non-surfer covering something so different from life on land and supported by so insular a culture. But like Jamie Brisick, who appears in “The Drop” doing surf therapy volunteer work with Ziolkowski, and Lewis Samuels, a former Surfline contributor who made the jump to Esquire to write about Kelly Slater’s wave pool, Ziolkowski is part of the small-but-growing number of talented writers who actually surf, and who increasingly receive assignments from non-surfing publications to write about surfing’s brushes with primetime. (This trend has likely been accelerated by the collapse of traditional surf media; Surfer Magazine, the “Bible of the sport,” ended its six decade-run of print publication in October of last year.)

“I think the main thing that has happened in the surf memoir evolution is that surfers started to write about surfing,” Ziolkowski said in an interview.

Finnegan has probably done more than anyone to make surfing the deserving subject of well-crafted literary nonfiction, and to establish the place of the surfing writer in such a genre. “Playing Doc’s Games,” his two-part 1992 New Yorker story, is about the San Francisco surf scene, and the obsessed figure of Dr. Mark Renneker. The trepidation Finnegan feels is not just for the life-threatening waves at Ocean Beach, but a harder-to-place concern for the way surfing can crowd out everything else in life, what he calls, in a phrase that surely resonates with any addict, surfing’s “disabling enchantment.”

Like Finnegan, Ziolkowski’s familiarity with surfing gives him an in to surfing’s hermetic world, and a command of details missing when non-surfers attempt to write about wave riding. He also shares with Finnegan an ability to love surfing without being blind to its flaws and failures — to be among the surfers, but not of them. In a review of the big-wave surfing film “Riding Giants” for ArtForum, Ziolkowski lamented the growing popularity of Jet Skis thusly: “Their embrace by the world’s best surfers makes it dishearteningly difficult to distinguish surfers from motocross knuckleheads destroying a forest or water-skiing frat boys at the local lake.”

Ziolkowski initially conceived his latest book as a collection of essays about surfing he had written for other publications, including The New York Times, but with a new capstone about death and surfing or some other topic.

“My agent said, You need to go bigger; I think you need to be more ambitious. And so when I thought about what would really push me, the overarching thematic of addiction was the one that made the most sense. That gave the book a sort of cohesion, and also some risk in coming out as an addict myself,” he told me.

The idea also allowed him to dive into addiction research, a surprising amount of which is now being conducted by recovering addicts. Among the most fascinating and unintuitive of these is the concept of “opponent processes,” which are the brain’s ability to limit the effect of drugs on subsequent uses, and the source of the addict’s doomed quest to match that first, magical high.

“The crafty, censorious brain produces biochemical countermeasures to countervail the high being predicted and foreshadowed. The brain can be temporarily and partially outfoxed if one takes the drug not late at night in the bathroom of a bar but, for instance, early in the morning in a cornfield — if that’s imaginable — but even then the shrewd, dogged brain will soon catch on and catch up,” Ziolkowski writes.

There is a clear parallel between the arms race of building drug tolerance, and the career surfer’s shrugging dismissal of waves that his or her 10-year-old self would have dived into with aplomb. In his recent book “Beginners: The Joy and Transformative Power of Lifelong Learning,” the journalist Tom Vanderbilt picks surfing as one of six things he will attempt to learn how to do in middle-age. (The cover of one edition of the book features an illustrated, three-step guide to surfing’s “pop up” that will be familiar to any Junior Lifeguard.) When discussing surfing, he arrives at the idea that it can be fun even if you’re bad at it. And in surfing, as with the rest of his chosen activities, Vanderbilt maintains the centrality of what has become popularly known as “beginner’s mind,” the ability to find joy in something even after the outer layers of rapid progress are peeled away.

If drugs are an antagonist to beginner’s mind, what is it that can make an experience feel renewing and healing? Central to the neuroscience of surfing, and the therapeutic promise it holds, is that, by temporarily forcing us from our familiar surroundings and into an immersion with nature, it gets us out of our heads and into a more empathetic mode. It breaks down what Virginia Woolf called “the shell-like covering which our souls have excreted to house themselves, to make for themselves a shape distinct from others.” Ziolkowski quotes Johann Hari for the idea that the opposite of addiction is “not sobriety but connection.”

Although his descriptions of the science are approachable and compelling, Ziolkowski clearly has mixed feelings about the notion of a solely chemical or physiological explanation for why someone becomes an addict, why surfing is so fun, and why the two groups overlap as much as they do. Even after writing the book, he remains uncertain about how an experience so profound sets off something tragic. If you know someone who has an addiction, reach out to him and talk about addiction recovery.

“I do wonder how darkness enters into something so totalizing and great. How do people end up being addicted to drugs as surfers? It’s almost like, not exactly the Problem of Evil, but the Problem of Paradise,” he said, contemplating the surfer who grows disillusioned with perfection. “Why is there that greedy need for more out of surfing, more thrill? What does surfing do to us that puts us on a track — perhaps, or perhaps not — toward a kind of greed for excitement?”

Thad Ziolkowski will be appearing in a Zoom conversation with William Finnegan put on by pages: a bookstore on July 6 at 5:30 p.m. To register, go to the store’s website. ER