Apocalypse Now, Apocalypse Then

Did Caspar David Friedrich really see into the future?

A speculative inquiry, by Bondo Wyszpolski

On the heels of major exhibitions across Germany in honor of his 250th birthday, Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) is finally getting the retrospective in the United States that he deserves. Some 75 works by this preeminent German Romantic will be on display in Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature through May 11 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Perhaps the most iconic picture on view is Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1817-18). It shows a smartly dressed man standing atop a mountain peak and gazing upon an open terrain that stretches far into the distance. We do not know who the man is; we see him only from behind.

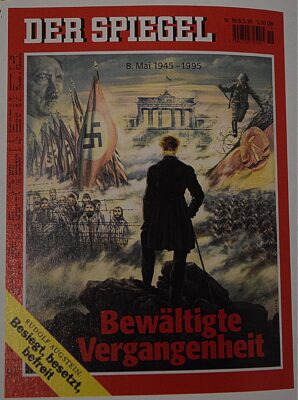

This same Wanderer graces the May 7, 1995 cover of Germany’s popular Der Spiegel magazine that marked 50 years since the end of World War Two. Bearing the caption, Bewältigte Vergangenheit (The Past Overcome), the peaks and valleys and low clouds have largely been overlaid with an unsavory collage of swastikas, soldiers, Hitler, and concentration camp inmates. In the catalog for last year’s Hamburg exhibition we read that the Wanderer is “compelled to look back at one of the darkest chapters in human history and its consequences.”

This same Wanderer graces the May 7, 1995 cover of Germany’s popular Der Spiegel magazine that marked 50 years since the end of World War Two. Bearing the caption, Bewältigte Vergangenheit (The Past Overcome), the peaks and valleys and low clouds have largely been overlaid with an unsavory collage of swastikas, soldiers, Hitler, and concentration camp inmates. In the catalog for last year’s Hamburg exhibition we read that the Wanderer is “compelled to look back at one of the darkest chapters in human history and its consequences.”

Do you notice anything odd in that description? If not, let me reference a few words spoken by the fictional Victor, a Dutch sculptor living in Berlin, in All Souls Day, by the novelist Cees Nooteboom. Victor says of Friedrich’s paintings that “when you look at those canvases, you look back in time. Friedrich himself looked forward.”

From that perspective, the Wanderer on Der Spiegel is envisioning or prophesizing a future that now lies behind us: His future, our past.

In the same novel, Arthur Daane considers the painter’s work and says, “You had to grant Friedrich that much: at least he had a suspicion… Art is nothing without a sense of foreboding.”

Granted, Victor and Arthur are fictional characters. So let’s find something more concrete. “After 1930,” Leonard Shlain wrote in Art & Physics, “art became pervaded by morbid images that seem in retrospect to have been predicated on some artistic premonition.”

That gets us a little closer. H.G. Schenk, in The Mind of the European Romantics, noted that, “As regards the Romantics themselves, it can be shown that many of them possessed that rare gift of inspired, or intuitive, insight that manifested itself in an astonishing presentiment of things to come.” And then, this: “Even the inhuman atrocities committed during the Second World War were somehow anticipated by the Romantics.”

This takes us back to the cover of Der Spiegel. I don’t wish to claim that Friedrich envisioned the horrors of the 1940s while he was quietly painting at home in the early 1800s. Besides, he wouldn’t have had the visual vocabulary to accurately depict these atrocities. But what I think we can say, to parse a line from Saul Bellow’s Ravelstein, is that the painter was someone who “pressed his ear to the rail and heard the locomotive coming.”

He wasn’t alone; there were others as I’ll show. You can take it or leave it. But if there was one important visual artist in the entire history of art who heard the distant rumbling of the future, and knew it didn’t bode well, that person was Caspar David Friedrich.

In 1798, the year he turned 24, Friedrich moved from Greifswald near the Baltic Coast and settled in Dresden, a jewel of a city, Florence-on-the-Elbe and so on. He more or less remained in Dresden until his death in 1840.

One can safely describe Friedrich as a mystic with a brush who embodied the austerity of a Zen monk. The room in which he painted was virtually devoid of all extraneous objects. The physician, author, and painter Carl Gustav Carus wrote that Friedrich’s life “was of a piece with his art, characterized by a strict integrity, rectitude, and reclusiveness… Incidentally, he almost continuously brooded over his artistic creations in his darkly shadowed room.”

It’s true that he grew anxious and depressed in his final years, his health and saleability on the decline, but earlier, as attested to by Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, “whoever saw in the painter Friedrich only his profound melancholy knew but one side of him. I have met few people who in the company of others whom they liked had such cheerful, easy-going ways and so much sense of fun. With a most serious expression he would talk and tell stories which produced endless laughter.”

After his death, Friedrich fell into near-obscurity, and this lasted nearly 60 years. Sadly, because he wasn’t in the habit of signing his paintings, many of them vanished. Some years ago Schmied wrote that “we know roughly 180 paintings of the possibly 300 that Friedrich created.” A handful of these have resurfaced, balanced by others that have disappeared. Several of his pictures were lost during World War Two. There’s a footnote in the catalog for Captured Emotions that informs us that in the 1945 firebombing of Dresden 201 works from the art museums were burned and that 556 are still missing.

As José Saramago put it in The Notebook, “In spite of what people usually say, the future is already written; it is just that we do not have the necessary science to read it.” Perhaps Friedrich could make out a few words, a couple of sentences, maybe a paragraph or two. I want us to look at four paintings, two still in our possession, and two existing only in old photographs. If Friedrich indeed glimpsed the future, these works may offer a clue.

Distant Thunder

First, it’s time for a disclaimer. By and large, the people who write essays and books about Friedrich have art degrees and teaching positions at notable universities or else hold curatorial positions at prestigious institutions. Not me. I come to Friedrich via the ladder up to the back window, with no training whatsoever about art. I would be the last person invited to a scholarly conference or symposium as I have no credentials to speak of. Empty pockets. That said, I’ve had several uncanny experiences where Friedrich is concerned, far too many to note, but one or two will have to suffice, beginning with the afternoon when I sat at home, leafing through one of my books about Friedrich and wondering if I’d ever get to see his works in the flesh. And it was then — then and not later — that a friend telephoned. He’d had a woman friend visiting from Germany and one of her friends had just arrived from overseas. Would I care to join them and others for dinner? Six months later both of those women greeted me in Hamburg after I stepped off the plane. Soon I was off for the island of Rügen, Greifswald, Berlin, Dresden, and Munich.

A year later, on another trip to Dresden I visited the cemetery where Friedrich is buried. I placed my business card behind his gravestone and said, not mincing words, Now it’s your turn to come and see me in L.A. About a week later, in Hamburg, I was shown a newspaper clipping: the J. Paul Getty Museum had just acquired Friedrich’s A Walk at Dusk. You see? Invitation accepted! Two years after this I was back in Dresden for the city’s commemoration of the firebombing 50 years earlier. I rarely have uncanny experiences, but that trip had its share. That was quite a while back, before the Frauenkirche, the Church of Our Lady, was rebuilt, although I’d seen it in three different stages before then, from fenced-off ruin to partial reconstruction. Dresden, like Friedrich, has now been rehabilitated. Today, if you didn’t know the history that culminated in the winter of 1945, you’d have no idea of what it went through.

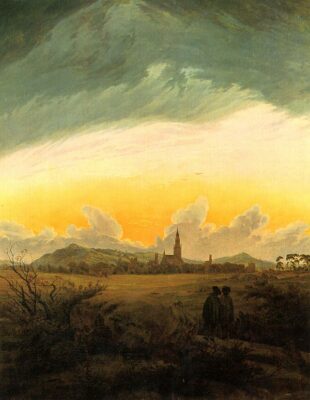

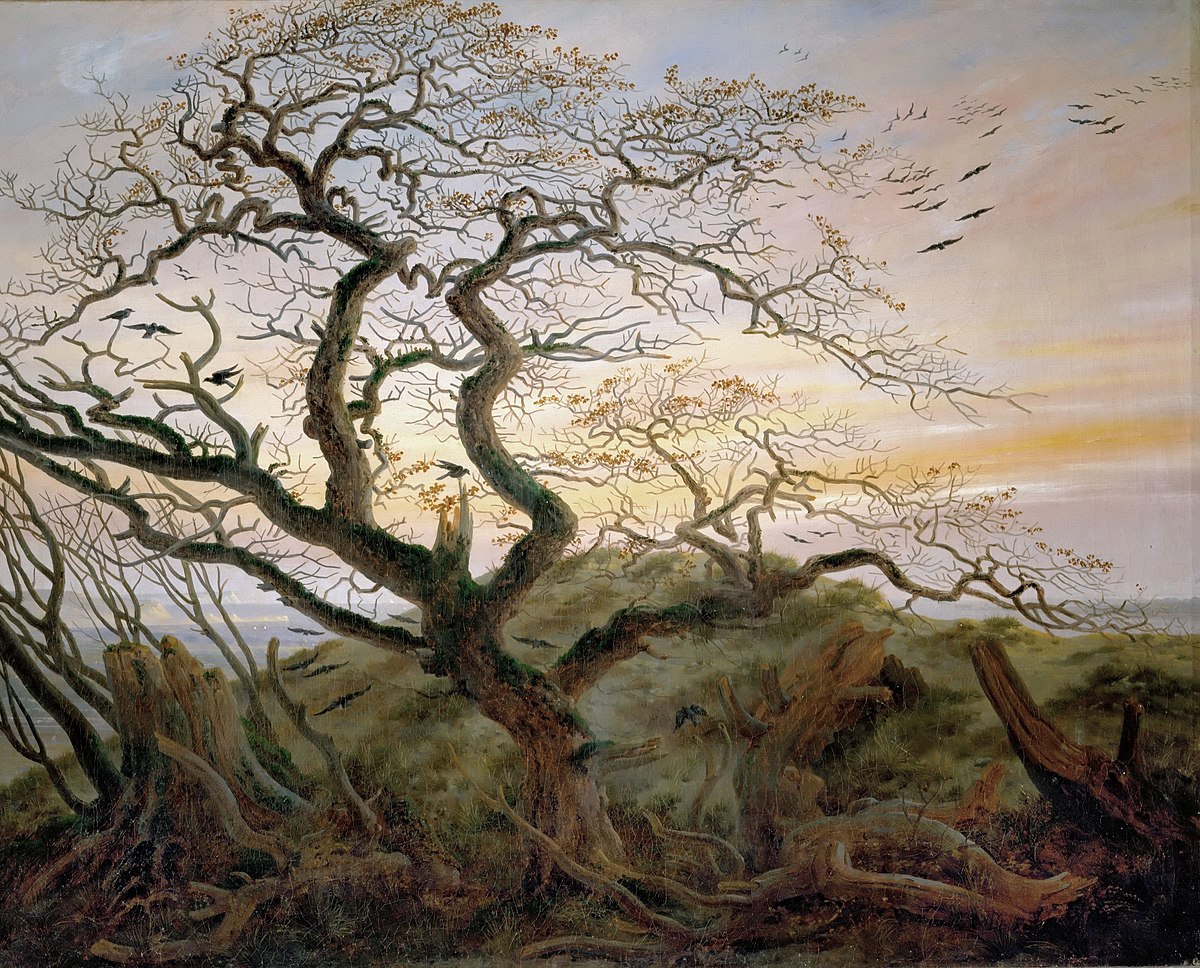

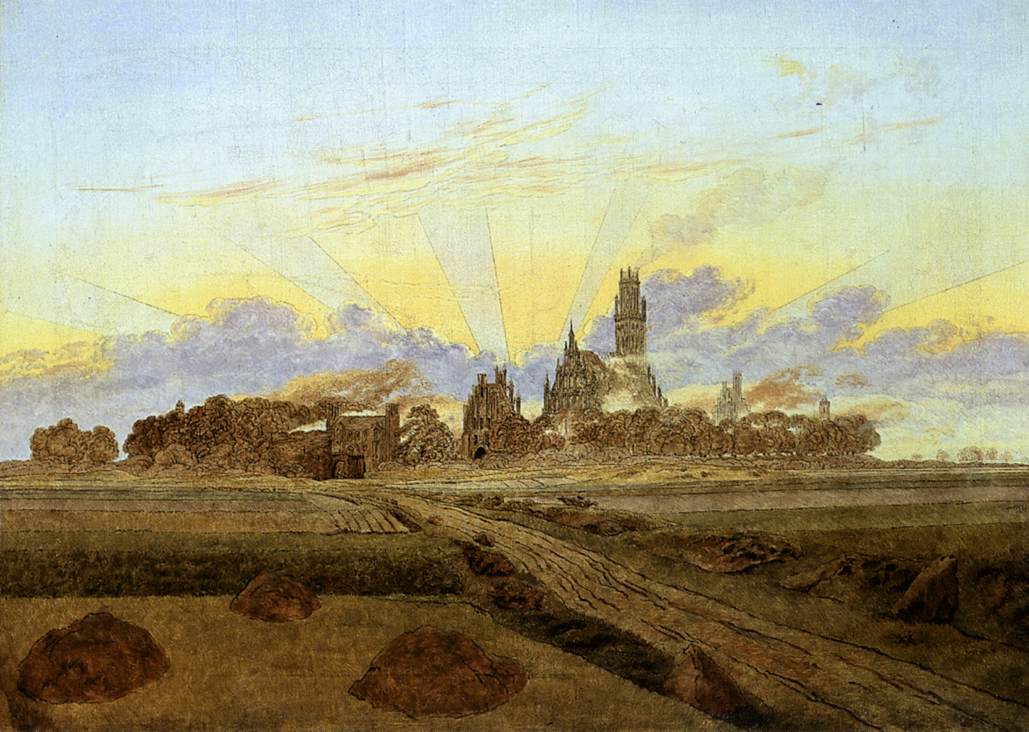

Neubrandenburg (or Neubrandenburg at Sunset; titles are always changing) was painted around 1817, and two travelers have halted between two large rocks, dolmen, I guess, which often indicate ancient burial sites, but here in addition they serve as a barrier or gateway from one realm into another (spatial recession in Friedrich’s work often suggests chronological recession, so many of his pictures are, to put it bluntly, four-dimensional representations). The men are looking across a plain towards the city of Neubrandenburg. “The sunset is so dramatic,” writes William Vaughan, “that it almost looks like an apocalyptic fire and has been read by some in eschatological terms.” Above this dramatic sky, and hovering like some terrible bird of prey, is a scramble of dark gray clouds. This is truly an ominous painting.

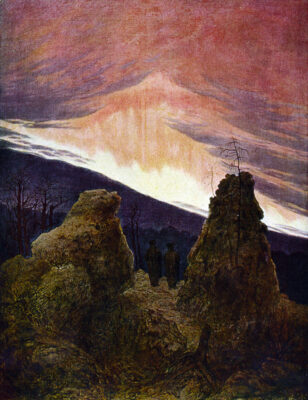

Some years later, in 1835, Friedrich began a picture, now in Hamburg, known as Neubrandenburg in Flames (or, more delicately, Sunrise near Neubrandenburg). It was left unfinished at his death. Essentially, the viewer is in roughly the same place previously occupied by the two travelers, although without the dolmen and without the hideous sky of the 1817 work. Nonetheless, as Norbert Wolf has pointed out, Neubrandenburg in Flames “portrays a subject that possibly contains an apocalyptic message,” although he doesn’t say what that message might be. What one sees, however, is that buildings in the town are on fire. Marcus Bertsch thinks the picture “reveals the… disturbing and visionary character of his [Friedrich’s] art. Nothing is known of a fire in the city during his lifetime, but Friedrich may have been alluding to any of the historically documented blazes of 1631, 1676, and 1737.” On the other hand, Helmut Börsch-Supan conjectures that “with the fire in the town Friedrich presumably intended to depict an allegory of the Last Judgment.”

Some viewers may find it of interest that it’s from the tower of the Marienkirche, the tallest structure in the skyline, that smoke is billowing. To make an allusion, and you can fill in the rest, Friedrich’s last New York exhibition, Moonwatchers, was scheduled to open on Sept. 11, 2001.

I may as well tell you now, but 90 percent of the Old Town of Neubrandenburg was destroyed on April 28-29, 1945. The new buildings there date from the 1950s to the 1970s.

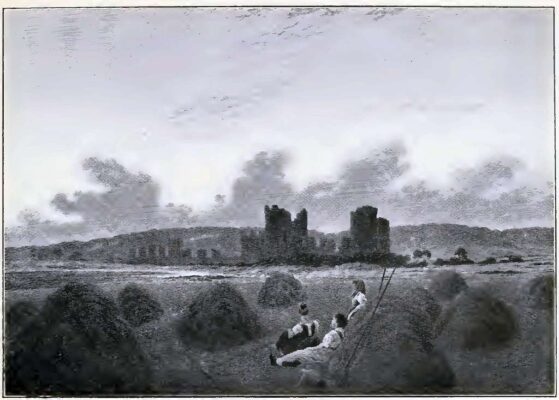

Ironically, then, the picture went missing (presumably destroyed) when Dresden was incinerated. Although the clouds, which emerge from behind the hill which frames the city, are the same clouds we see in Neubrandenburg, the expanse of ruins depicted, and one might think of them as smoldering ruins, are not those of Neubrandenburg but of the castle ruins of Landskron, near Altentreptow, which date to the second half of the 16th century. Friedrich sketched them in 1801, and later appropriated the drawing for Haymakers at Rest. The figures of the title, apparently two women and a man, have finished their labors and are sitting or leaning back against one of the haystacks and seem to be facing towards what could be a sunset or even an approaching storm. Friedrich’s clouds and dark skies are often operatic as if portending something dangerous.

These four works, related to one another by the fact of their having been conceived and painted by the same artist, with elements in each that seem to cross-reference one another, recalls the final scene of Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming, by László Krasznahorkai, in which there’s an entire city in flames being watched by the Idiot Child who sits atop the water tower on the outskirts of town: “And at the end he looked up to the sky, the darkening sky, raising both his hands…”

There’s more that one could stir into this kettle, for example Friedrich’s visionary cathedrals in contrast to his depictions of still-extant structures as ruins — the Saint Jacobi Church in Greifswald or Meissen Cathedral. I mentioned that he wasn’t alone in hearing that distant rumbling, and in this particular case it mostly came from artists who lived, even briefly, in that jewel of a city, Dresden.

In a letter dated Jan. 3, 1917, Hermann Hesse says: “I feel that writers, artists, etc., such as myself, act as the antennae or early-warning posts of mankind and are the first to sniff any new developments. The artists then describe that new world, even though nobody is willing to believe in it yet, and they themselves cannot implement it.”

Artists who have the capacity — shall we call it a gift or a curse? — to sniff out new developments may bear a heavy burden. After all, when you have premonitions of disaster it’s like you end up suffering through them twice. And so in Dresden, in the early 1800s, there was a certain fatalism that appears to have manifested itself in a variety of singular works. The few people I want to mention are well-known, but presumably there are more in the wings, waiting to be discovered. This handful, however, has some connection, direct or indirect, with Caspar David Friedrich.

Norbert Wolf calls the painter’s The Monk by the Sea (c.1809) “the boldest picture within German Romanticism as a whole.” The writer Heinrich von Kleist, noted Wieland Schmied, “was the first to record a deep emotional response to one of Friedrich’s paintings;” and what Kleist said, among other things, is that “The picture… lies before us like the Apocalypse.”

The highly sensitive Kleist was one of the attuned, and the pall of hopelessness in Friedrich’s canvas resonated within him. Rüdiger Safranski mentions Kleist and the “annihilation fantasies” that emerge in some of his works, adding that “No other writer of the nineteenth century represented the act of killing with such libidinous exactitude as Kleist.”

Indeed, in his short story, “The Earthquake in Chile,” a few lines grasp at utter destruction, such as “the greater part of the city suddenly collapsed with a roar, as if the firmament had given way, burying every living thing in its ruins,” and “Here another house crashed down, hurtling wreckage all around… here the flames were licking out of all the gables, flashing brightly colored through the clouds of smoke…”

Kleist took his own life in 1811, at the age of 34.

In the discarded second draft of Woyzeck, by Georg Büchner, the troubled Woyzeck says to his doctor, “Don’t you hear the terrible noise in the sky? Over the town it’s all in flames! Don’t look back. Look how it’s shooting up, and everything’s thundering.”

Büchner’s characters are out of step with the world, marching to their own drummer much like Bruno S. in Werner Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (or Every Man for Himself and God Against All), a film that adapts Woyzeck’s cri de coeur: “Don’t you hear that horrible screaming all around you? That screaming men call silence?”. Later, having filmed Büchner’s drama (Woyzeck, with Klaus Kinski), Herzog said in a 1996 interview that “Much of what you see when you read Büchner’s Lenz, or Kleist, or Hölderlin, is the innermost landscapes of human beings, and that is why they will outlive everything else.”

Now we come to a pair of more substantial characters, the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and the composer Richard Wagner.

I’m not sure if Schopenhauer, who was born in 1788, ever met Friedrich, although his mother, Johanna Schopenhauer, rather well known in her day, was personally acquainted with the artist.

Bertrand Russell noted that Schopenhauer is the most readable of the German philosophers, but the great pessimist in a candy wrapper is how I would describe him. And while a little Schopenhauer never hurt anybody, a lot of Schopenhauer can kill you. H.G. Schenk might have agreed: “The futility of life is also the dominant theme of Schopenhauer’s gloomy philosophy, but here such depth is reached that, in some ways, his nihilism has a strong diabolical tinge… All in all, the world appears as the worst of all possible worlds.”

Schopenhauer lived in Dresden from 1814-1818 and that is where he wrote The World as Will and Representation, published in 1819 (Warning: If you’re young and impressionistic, don’t read it). “In retrospect,” Safranski writes, “Schopenhauer was to describe his four years in Dresden as the most productive of his life.”

Was there something in the aether? Because it’s here that the whole system of his singular philosophy coalesced and poured forth.

Now entering the twilight zone

And so on to Richard Wagner, born in 1813. Like Schopenhauer, he spent a few vital years in Dresden, but, coming later, may not have known about Friedrich. At any rate, Friedrich was quite dead by the time Wagner was introduced to Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation in 1854. He apparently then read it several times, at least according to Michael Tanner’s monograph, Wagner. As a result, Wagner and Schopenhauer communicated, but the latter was more of a Rossini-Mozart kind of guy and Wagner, well, Wagner was a composer on a much different footpath.

Wagner, like Schopenhauer before him, had his important Dresden years, and it’s where his operas Rienzi (1842) and The Flying Dutchman (1843) were premiered. Also, while in Dresden, he composed Tannhäuser and Lohengrin and, as Frederick Taylor notes, “He started to map out what was later to become the Song of the Nibelungen.” As for those earlier operas, Rienzi ends with a catastrophic fire and The Flying Dutchman abounds in premonitions. Senta, for example, has an interest in and knowledge of the Dutchman before he steps ashore, and he, too, senses that she’s the one he’s been seeking.

Of course, it all really boils over in Götterdämmerung, the fourth and final opera of the Ring cycle. In his program notes for L.A. Opera’s production, performed in 2010, conductor James Conlon states that “Both as music and theater Götterdämmerung stands as the most massive achievement in apocalyptic art.”

Well, that could be, and Harry Kupfer’s 1988 Bayreuth production of the Ring did conclude with a nuclear holocaust (as if the ring itself had something or everything to do with the secret of nuclear fission), but before we get to that point we should consider the ravens. A pair of them appear in Act II, Scene III, and when Siegfried turns away from Hagen to look up at them Hagen spears him in the back. Later, when Brünnhilde has removed the ring from Siegfried’s finger and is about to return it to the Rhinemaidens, the ravens reappear. Brünnhilde instructs the birds to tell Loge (the god of fire) that the time has come to set Valhalla aflame. Valhalla then explodes and the resulting conflagration is as great as the one that consumed Dresden on Feb. 13, 1945, on what was Wagner’s 132nd birthday.

On one of my trips to Dresden, I went to the home, now a museum, of Gerhard von Kügelgen, and on display was an early portrait of Friedrich by Caroline Bardua. The painter Kügelgen was a good friend of Friedrich’s until he was murdered by highwaymen in 1820; Bardua painted many of the era’s elite, including Carl Maria von Weber, Goethe, and Johanna Schopenhauer.

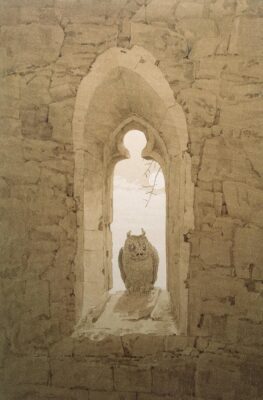

While standing in front of Caroline Bardua’s portrait of Friedrich it struck me that at some point, perhaps while the portrait was in progress, maybe before or after, the two of them must have shared a laugh when Caroline Bardua told her subject that he resembled an owl. That’s your bird, Fred. So I think that both Rewald and Hess may have sensed this as well, and it comes to fruition in Friedrich’s late and very large sepia, Owl on a Coffin, in which the full moon is positioned just over the owl’s head, between the tufts of its two ears. You see, I believe that canvases are conduits, mediums of a sort, between artist and viewer, and sometimes we can “hear” something. As Basho wrote, “The temple bell stops / but the sound keeps coming / out of the flowers.”

By some coincidence, because this is not my usual sort of reading matter, I came across Voices from the Cosmos by Angela T. Smith, a woman who recorded her conversations with extraterrestrial beings, and I was struck by these words, as communicated to her by the Aldebarans: “One thing to remember is that every catastrophe or major event sends ripples in time both ahead of itself and behind it. Humans already know this. So, look for the ripples that will indicate something big is about to happen. There are many sensitive Humans who are able to detect these ripples.”

Well, a trump is a trumpet, but is “The Second Trump” a certain individual’s return to the presidency of the United States?

Think back to that Wanderer standing on a mountain peak and looking into the distance. Is he seeing something that is not yet available to the rest of us? I don’t know; all of the above is merely speculation, wheat and chaff combined. As Friedrich himself said, “Art may be a game, but it’s a serious game,” and that’s how I approached this story.

***

I’m thinking Baron, wandering, towering over more than just most; The Second Trump.