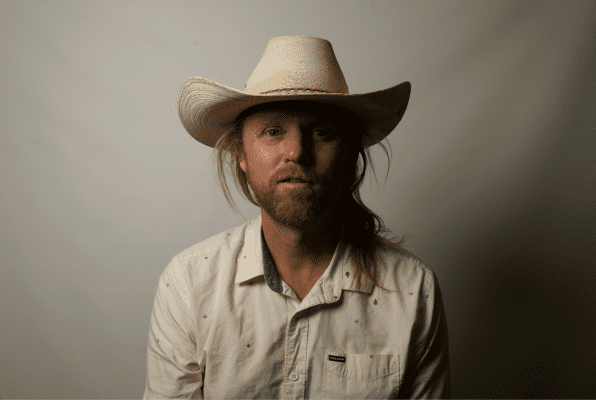

Olympic triathlete Taylor Spivey traces success to JGs

by Kevin Cody

Among the most heartwarming congratulatory notes Taylor Spivey received after qualifying for the 2024 U.S. Triathlon Olympic Team last month were from her former Junior Lifeguard instructors, and the Junior Lifeguards she taught after she became a Los Angeles County Lifeguard.

Spivey credits her lifeguard training with her success as a professional triathlete.

“Without my first JG instructor, Heidi Nelson, (then the only female on the Lifeguard Taplin Relay Bell), to my last JG instructor, Jason May (triathlete, and Redondo Fire Captain), I wouldn’t be the athlete I am today,” she told Racemill.com in a recent podcast.

Spivey expanded on the role ocean lifeguarding played in her becoming an Olympic athlete during a phone interview last week from Font-Romeu-Odeillo-Via, in the French Pyrenees, where she is training.

She described herself as “super competitive as a kid” growing up in Manhattan Beach.

“I played AYSO soccer, snow boarded, swam and played water polo at Mira Costa High. I was late to triathlons because Manhattan Beach didn’t have triathlons for kids, like they do in Europe.

“But I had Junior Lifeguards, from the time I was nine until I was 18. It laid a foundation for me. I was surrounded by like-minded, competitive people who were like family.”

Spivey also benefited from good genes.

Her mother, Bonnie, was a lifeguard, and professional triathlete, who now coaches swimmers. At the 1989 Canadian Ironman, she set the Ironman Swim World Record. The following year, she competed in the Canadian Ironman while pregnant with Taylor, validating Taylor’s claim to have competed in her first Ironman before she was born.

Both Spivey’s mother and father said they were more inclined to temper their daughter’s competitiveness, rather than encourage it.

Bonnie Spivey remembers her daughter trying desperately to pass her when she was running on The Strand, her daughter was on a bicycle, with training wheels.

Her parents met at a triathlon, which her father, Marc, also competed in.

Her dad remembers congratulating his daughter on finishing second in her first Pier to Pier Swim, after she became a Lifeguard. The legendary lifeguard and open ocean swimmer Diane Gallas passed Spivey as they approached the finish by catching a wave.

“Taylor burst into tears. Second place wasn’t ever going to be good enough for her,” her dad said.

Spivey attributes her climbing and group riding skills to Sunday “Wheatgrass Rides” with her dad and his fellow “roadies.” The Palos Verdes hill climbs were always followed by a shot of wheatgrass at the Jamba Juice at the top of the Peninsula, courtesy of attorney, and her dad’s fellow roadie, Mike Norris.

“Those old guys still kick my butt,” Spivey said.

At 5-foot-3, 110 pounds, Spivey is, as she puts it, petite. Nelson, who is in her 30th summer of coaching JGs, remembers nine-year-old Spivey as “a little peanut. But her size didn’t stop her from charging into the surf. I tell the kids, lifeguarding is about technique, not size,” Nelson said.

Spivey was named Outstanding Rookie when she completed the Lifeguard Academy in 2009, the year she graduated from Mira Costa.

In 2011 and again in 2012 she won the women’s Ocean Lifeguard National Championships. The competition includes running, swimming, paddleboarding and surf skiing.

The Olympic Triathlon consists of a 1500 meter swim, a 40 kilometer cycle, and a 10 kilometer run. It is scheduled for Wednesday, July 31 at 8 a.m. Paris time (nine hours ahead of Pacific Coast Time).

Spivey will also compete in the Mixed Relay Triathlon, on Monday August 5, starting at 8 a.m., Paris time. The mixed relay teams consist of two men and two women. Each team member swims 300 meters, cycles 6.8 kilometers and runs two kilometers.

There are no preliminary heats in the individual Olympic triathlon. All 55 competitors in the individual triathlon start the race at the same time.

The cycling course is seven laps through Paris streets, including cobblestone streets. The running course will be four laps through city streets.

But first comes the swim in the Seine River, which cuts through the heart of Paris. Swimming in the Seine has been banned since 1923 because of pollution. According to the Associated Press, France has spent $1.5 billion to make the Seine safe for the triathlon and the Olympic 10K Marathon Swim. But a June 21 report published by Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s office found the Seine still unsafe to swim in. French President Emmanuel Macron and Mayor Hidalgo have said they will swim in the river to prove it’s safe. But as of July 3, neither had done so.

Spivey dismissed the controversy as the usual pre Olympic grumbling.

“The same complaints were made about the water before the Rio de Janeiro Olympics in 2016 and the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. I’m confident the French will make the water safe,” she said.

As a lifeguard, Spivey contended with just about every imaginable water condition.

Her primary hope, she said, is that the water not be too warm, or too cold.

As an ocean swimmer, she prefers cold water. But the rules allow swimmers to wear wetsuits if the temperature is below 68 degrees. Wetsuits benefit weaker swimmers because of their buoyancy.

“Wetsuits make the triathlon more about running, than about swimming and biking,” Spivey said. The reason is wetsuits narrow the gap getting out of the water between strong swimmers and weak swimmers, she explained.

“Everyone starts fast in the swim. But after the first 100 meters swimmers who are fast but lack endurance fall back. I’m usually in the top five coming out of the water and getting to the transition area.

“That leads to a breakaway on the bikes, a small group that works together to gain an advantage going into the run,” she said.

Spivey learned during the 2011 Dwight Crum Two Mile Pier to Pier Swim the importance of drafting with the lead pack. She won the Pier to Pier women’s division that year, but could have been the first woman to win the two-mile swim, overall, had she been able to draft the whole race.

She described what happened during an 2011 Easy Reader interview following the race.

“I got sandwiched between two big guys rounding the Hermosa Pier (where the swimmers bottleneck).We were elbowing one another and one of the guys apparently got fed up and basically tried to climb over me. He literally pushed me under and held my head down long enough for me to freak out a bit. I guess he didn’t like getting ‘chicked,’” she said.

As a result she fell out of the lead pack and couldn’t draft until she caught up with the pack at the second-to-last lifeguard tower before the Manhattan pier, about half a mile from the finish. She finished fourth overall, just 22 seconds behind 10-time Pier to Pier winner Alex Kostich.

Though Spivey swam at Mira Costa and Cal Poly, she doesn’t consider swimming her strength.

“I’m known as a well rounded triathlete. You can’t be good at just one thing. And you need the right body type,” Spivey said.

She’s short but not unusually so for a triathlete.

“Triathletes aren’t generally tall, like swimmers. They’re lean and strong,” she said.

The sports’ commentators describe Spivey as a “tactical racer.”

“It’s being aware of the people around you and knowing when to push hard, but without totally exhausting yourself,” she said.

The importance of tactics is evident in how narrow the difference is between medaling and not medaling.

In last year’s World Triathlon Championship Series in Cagliari, Italy, Spivey finished the swim one second ahead of eventual winner Georgia Taylor Brown, of Great Britain, who won the silver medal at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. The two had identical times in the cycling leg, but Taylor Brown beat Spivey by 53 seconds in the run to claim first place in an overall time of 1:46:43. Despite being just 52 seconds behind the winner, Spivey finished third. Emma Lombard, of France, finished second, 37 seconds behind the winner. Cassendre Beaugrand, of France, missed the podium, finishing eight seconds behind Spivey.

Spivey missed the Tokyo Olympics by one spot, for which the US Olympic Triathlon Federation was widely criticized.

“I was the first or second American in every race leading up to the 2020 Olympics, and was ranked number one in the world in 2021,” she said. (The 2020 Tokyo Olympics were delayed to 2021 due to of COVID).

“I lost a lot of faith in the federation, but I continued to work hard and this year was chosen for the team by a unanimous vote,” she said.

Spivey was 22, in 2013 when she entered her first triathlon with the Cal Poly team.

“I was studying architecture and planning a year abroad, in Florence, and wanted a way to stay active, and meet Italian athletes,” she said.

When she returned in June of that year she entered the Redondo Beach Triathlon and won by four minutes, nearly a mile ahead of the second place finisher.

Then, in only her second year of triathlons, she won the USA Triathlon Collegiate National Championships. That led to an invitation to join the U.S. National Triathlon Team.

Spivey turned pro in 2015, but continued working as a recurrent (part time) Los Angeles County Lifeguard to support herself.

The sport of triathlons is ahead of most other sports in terms of gender equality, Spivey said. Men and women receive equal prize money and exposure. But that equality doesn’t extend to appearance fees, and sponsorships, where men receive significantly more money. (An early Spivey sponsor was Manhattan Beach-based Skechers.)

Despite ranking fourth or higher in four of the past five years in the World Triathlon Championship Series, she said, she still struggles to get sponsors.

Spivey lives and trains with the international Triathlon Squad, coached by Portuguese-born coach Paulo Sousa, in Girona, Spain. She is spending the five weeks leading up to the Olympics training at nearby Font-Romeu, a mile high ski resort in the French Pyrenees.

Training in the thin air gives a boost to athletes when they return to sea level, she said. Paris is 114 feet above sea level.

Spivey will continue triathlon competitions after Paris, and hasn’t ruled out competing in the Los Angeles Olympics in 2028.

“The LA Olympics seem far away, but it would be cool to participate at home, in front of friends and family. I’ll see how the body holds up,” she said.

When she began competing in triathlons, her first triathlon coach, Greg Mueller, warned her swimmers are susceptible to leg injuries because swimmers tend to go out too fast. Or as her dad’s cycling friend, Norris, himself a former swimmer, once told her, “Start fast, maintain the pace and sprint to the finish.”

Spivey has disregarded Norris’s advice, and followed Mueller’s direction to be careful on runs. As a result, she has rarely been injured. But last year she suffered her first stress fracture, of the tibia.

The only time Taylor has competed professionally at home was in 2022, at the Super League Championship Series event in Malibu. Her win in the local race put her in second place in the world that year.

Both the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics Triathlon swim and 10K Marathon Swim are planned for a rectangular course inside the Long Beach Breakwater, a venue sure to resurrect the pollution controversy.

In 2019, then Redondo Beach Mayor Bill Brand organized the Redondo Open Ocean Challenge to showcase Redondo as a site for the 2028 Olympics 10K Swim. The race was sanctioned by WOWSA (World Open Water Swimming Association) and widely praised by swimmers. WOWSA’s president, Steve Munatones, subsequently pleaded with the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to move the 2028 Olympic Marathon Swim from Long Beach to Redondo Beach.

“If the County of Los Angeles is going to spend billions of its money on presenting the Olympics to the world, I feel it is optimal and wise to showcase the best of Southern California. For anyone who has swum, surfed, kayaked, paddle boarded, fished, scuba dived or sailed off the coast of Palos Verdes and Redondo Beach, they will understand how beautiful and dramatic the marine environment is,” Munatones told the Supervisors during his 2021 presentation.

The Redondo Open Ocean Challenge has evolved into the annual one mile Swim the Avenues race, organized by Redondo Triathlon directors Mike Ward, owner of Village Runner, and Rick Crump, a P.E. teacher at Adams Middle School in Redondo Beach.

Swim the Avenues attracts over 600 swimmers annually, making it one of the largest open ocean swims in the country. But Redondo has yet to convince the Los Angeles Olympic Committee that an open ocean course from Redondo to Palos Verdes that thousands of spectators could watch from the Esplanade is better for athletes and spectators than a triangular course inside Long Beach Harbor, which like the Seine in France, generally prohibits swimming.

The Los Angeles River discharges an average of 207 million gallons a day into the Long Beach Harbor, according to a Los Angeles River Revitalization report.

Spivey said an Olympic triathlon in Redondo in 2028 would be an inspiration not only to her but to triathletes world wide.

The Olympic Triathlon’s 1.5 kilometer swim is coincidentally the same one-mile distance as the Swim the Avenues race, which spectators watch from the blocks long, oceanfront Esplanade.

The Olympic Triathlon’s 40 kilometer cycling distance is almost the same distance as the 24-mile “Donut Loop” through Palos Verdes that her dad and fellow roadies follow during their “Wheatgrass Rides.” The “Donut Loop” begins in Redondo, just a few blocks from the Swim the Avenues’ finish.

The final leg of the Olympic Triathlon, the 10 kilometer run, could follow the annual Redondo Beach Super Bowl 10 route, which spectators also view from the Esplanade.

A Redondo Olympic triathlon would be a homecoming in more ways than one for Spivey. Redondo is where she taught Junior Guards. ER