Passion projects

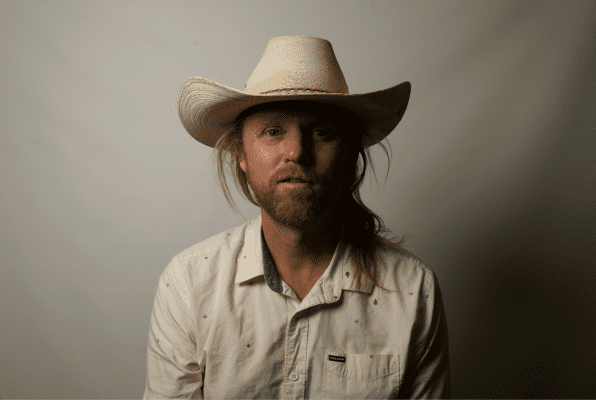

Conversing with photographer Patrick Smyth

by Bondo Wyszpolski

Intrigued by the grimacing heads sculpted by Franz Xavier Messerschmidt in the late 18th century (and by the Getty’s “Vexed Man” in particular), Reidar Schopp invited several photographers to his San Pedro studio in order to shoot one another in facial poses — frowns, scowls, sneers — that would have made Messerschmidt proud. I too was invited, to stop by and observe, but pretty soon I’d entered the fray and was posing and photographing as well.

Therefore one would expect to hear tales of art classes, darkroom adventures and photography courses, let alone accounts of hours spent in photo galleries. But, no, it didn’t unfold in quite that way.

“I’m a full-time chemical engineer,” Smyth says, “and this is just a passion I have.”

If so, it’s a passion that most people — and I think most photographers — would envy.

Smyth was born and raised in a town of about a thousand people, tucked away in mid-America Kansas.

And you’ve been an engineer all that time?

“Yes.”

So you should be retiring at some point soon?

“Well, I’m still enjoying it,” Smyth replies. “I like mentoring the young engineers. I want to be in a position to retire to something, not necessarily away from something.” And what that means is: “Photography and more photography and travel.”

Homeschooled

Looking at Smyth’s body of work, one may be forgiven for assuming that he also has a background in the visual arts.

“I’ve never studied art,” he says, only adding that while he did indeed enjoy art class in grade school, he was more into sports. However, trips as a youngster with his family to the mountains and so forth instilled in him “a sense of wildlife and landscapes.” And one doesn’t need a Ph.D. from Harvard to appreciate the beauties of nature.

“I’m self-taught,” Smyth replies afterwards when asked where he learned his photographic expertise. He also notes that one can pick up pointers from YouTube. That said, he’s acquired some personal instruction along the way.

But it was also while in Italy that Smyth sought out the paintings of Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1571-1610), known for his chiaroscuro and accentuated shadows.

“I don’t follow particular photographers,” he answers when asked, “but I like to go back to the masters in painting, and really draw inspiration from them.” As for Caravaggio, “I’m intrigued by his darks, and then the tenebrism. I really just discovered that as I started to shoot portraitures.”

And so, while in the Tuscany workshop, which utilized two professional models (a blonde, Leo Leblanche, and a brunette, Mischkah Scott), Smyth was mindful of what he’d observed in the Caravaggios, and I think it’s an influence that he’s called up and utilized, to some degree, ever since. It’s often a mixture of stark lighting and deep shadows.

“Ellen’s just been great to work with,” he says, and receptive to his ideas as they try out one pose or another. “Some things will work, some things won’t. I’ve learned that, when you’re shooting a ballerina, what looks great to me may not be technically right for them.” But one thing’s for sure, he’s come up with some striking images of Ellen and hopes there’ll be more.

Wearing many hats

On his website, Smyth’s photographs are grouped by category, and there are quite a few of them: People, Wild Life, Scenics, Fine Art, Fashion, Fun, Places, Flora, Things, Macro, and one called the 100 Hats Project. But is there one category among these that he prefers above the others?

“I found myself not wanting to be in a certain genre,” he says, “and that’s why I have these categories. I’m kind of looking for shiny things, beautiful things, and so it’s not important for me to stay or hang in a certain niche. I think it opens up more of the world in photography,” and he mentions his Macro category which represents his photographic foray into the microscopic world. So in case you were wondering, it’s not all Stonehenge and dancers. “Things like that,” Smyth says, summing it up, “continue to keep it fresh and different.”

And then there’s the 100 hats project, which began as a way of challenging himself, perhaps to test his personal comfort zone, because he’s been reluctant to simply walk up to people and ask if he can take their picture.

Smyth isn’t really thinking of assembling his hat photos into any sort of publication. “I did it just pretty much for me,” he says, “but at the same time there are so many stories behind the pictures.” Later in our conversation he says that maybe in his retirement he’ll gather some of those stories together, and then who knows what’ll happen after that.

Although he professes to be drawn to a multitude of subjects, my impression is that he’s more attuned to portraiture, or “the human element” as he puts it. Remember what Smyth said earlier, that after he’s set chemical engineering behind him what he’d like to pursue is “photography and more photography and travel.”

“I could have seen myself being some sort of fashion designer,” Smyth says. “I probably couldn’t do it, but I’m intrigued by fashion.”

Retirement, when it comes, is going to open up lots of doors, a lot of photographic possibilities, and Smyth will be ready for them.

To see more of Patrick Smyth’s work, visit his website at digitalsmyth.com. PEN