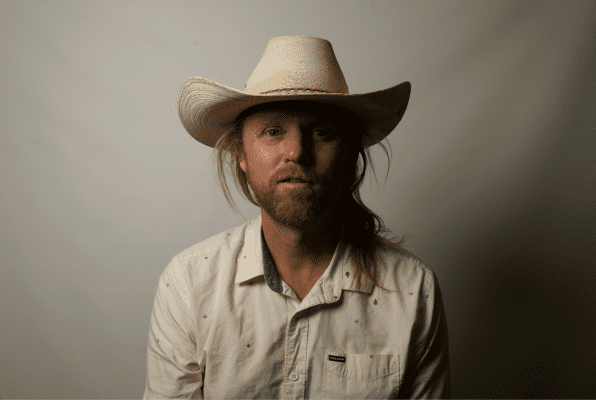

A man who loved beautiful things

Rodney Smith: A Leap of Faith, by Paul Martineau (Getty Publications, 248 pp; $65)

by Bondo Wyszpolski

This is as much a luxury item as it is a volume of elegant, bewitching photographs, and it complements similarly-related books that Getty curator of photographs Paul Martineau has written for the institution’s publishing arm, in particular “Icons of Style: A Century of Fashion Photography” and “Herb Ritts: L.A. Style,” the latter also being catalogs in tandem with major exhibitions.

Smith may be described or summarized as an American fashion photographer, but he was also one with an occasional playful touch. The humor, though, is restrained, held in check; he’s not fishing for the belly laugh. Graydon Carter (formerly an editor of Vanity Fair for 25 years) describes the look of a Smith photograph in these words, or rather this equation: “Wes Anderson + René Magritte ÷ Federico Fellini – Irving Penn = Rodney Smith.” He also adds that “A Rodney Smith (image) can be whimsical but solemn, composed but candid, still but full of movement, mysterious but revealing, desperate but funny.”

Many of Smith’s later images have Gatsby-like young men and women in them, as if he was drawn to the New England jet set and edging closer to becoming something of a John Singer Sargent or William Merrit Chase of the fading millennium.

His earlier work, however, shows what he picked up from Walker Evans, who was one of his teachers, and, for example, a trip to Israel in 1976 — which yielded several timeless images — no doubt enhanced his eye and sharpened his sensibility. Tone, focus, visual texture, we see it in these pictures and also in those which he took in the American South, the United Kingdom, Haiti and France. Later, the poor people and the elderly would vanish from his work, but because they were there at the start they remain part of his artistic foundation.

As the above indicates, there were stressful times in Smith’s life, as there are in all sensitive people when the world at large places demands on them and has high expectations. But in photography Smith found his raison d’être, which was to create striking images.

To do this, though, a certain sensibility is required, and Smith appears to have had an intuitive sense of composition, the ability to take in all at once the shadows, shapes, colors or tones, and how they conspire with one another in some kind of harmonious fashion. And one has to be quick about this. There’s no time to hesitate. One sees, and must seize the moment.

It probably wasn’t difficult for Smith to slide into fashion photography because he’d done all the legwork, so to speak. He’d excelled in depicting quiet, serene, thought-inducing work, and so the sublime shifting into the elegant may perhaps have been a natural progression rather than, to reference the title of the book, making a leap of faith. Also, Smith apparently had a knack for getting people to relax and loosen up, which can pave the way into a successful photo shoot. One could say this is the first step, that of human interaction. Martineau talks about this in the book, when Smith was hired to make a series of corporate portraitures.

Not surprisingly, then, Smith focused on classic fashion. He avoided or perhaps turned down shooting the Halloween costume styles that we often see on fashion runways, worn by anemic models, and one doubts that he would have been tempted by the celebrity peahens and peacocks of the annual Met Gala. Also, too, there are no titillating images in Smith’s fashion photography. One could contrast his work with Tim Walker’s, currently on view at the Getty Center. Both men mastered their craft, but their work is light years apart.

This book is a lovely homage to the memory of a brilliant and sensitive photographer, and Paul Martineau, you are to be commended for bringing him to our attention. ER